A residency is the artist’s equivalent of a sabbatical: an opportunity to temporarily leave an accustomed workplace and work in an unfamiliar setting. Artists’ residencies are usually sponsored by communities, educational institutions, or — occasionally — private organizations. The discipline, practice and art of improvisation have been at the heart of my work for over fifty years. More recently, residencies have offered me some of the most inspiring and immediate opportunities for the creation of installations and performances. |

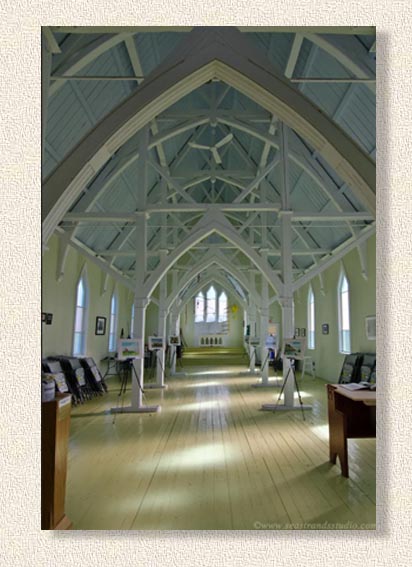

In

2000, artist Vida Simon and her partner Jack Stanley encouraged me to

take up a two-week residency in English Harbour, a fishing village on

the southwest shore of Fortune Bay, Newfoundland. The English Harbour

Arts Centre would provide a little house in the village and offered me

the

upstairs room of a seaside “fish store” — where fishermen

stored their gear — as a working and exhibition

space. The Arts Centre itself was a finely renovated former church and

would be available as a performance venue.

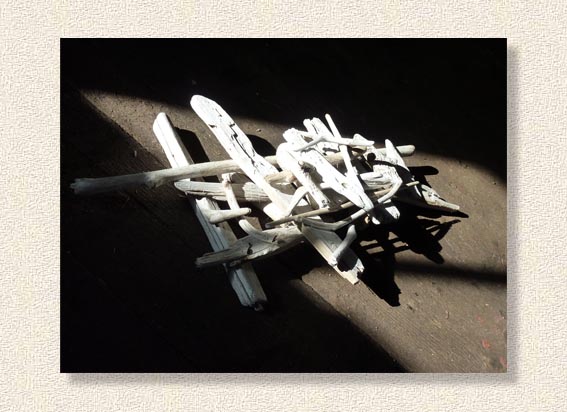

I arrived in Newfoundland with no concept of what I might find or do, and no materials other than ink, chalk, and a roll of rice paper. The ground floor of the fish store was crammed with fishing equipment; the upstairs windows had not been washed for decades and the structure never wired for electricity. I was excited already.  For the first week I wandered the shore, stopping to pick up driftwood here and there and adding rusty and discarded iron detritus from fishing work long past. I began to fall in love with each piece — something of a habit with me — and took them back to the upstairs “gallery”, where I would spend hours getting to know the space, the found objects, and reading Newfoundland poetry. As the days went by, I’d take time to sit outside and capture passing clouds with washes of ink on paper. I'd never undertaken anything like an installation, but over the course of the second week I gradually assembled these delicate discoveries into little sculptures. I chalked the surrounding walls with words that leapt to mind in that place, hung stone clouds from the ceiling, and on the ascending risers of the wooden stairway wrote “and we too come and go like the clouds.”  Upon completion of what became ‘The House of Clouds and Other Ephemerals’, the Arts Centre put up posters and about a dozen people showed up for an "opening" in the Arts Centre itself.  I returned home, leaving the installation in place for others to happen upon over the weeks to follow. I’d been back about a month when Stan Dragland contacted me with what he said was sad news. “A storm has swept the whole fish store into the water,” he told me. “Thank you, Stan,” I laughed out loud. “I just can’t imagine more perfect news.” |

Shortly

after my late husband Richard’s death, a close friend introduced me to

Csaba and Suzanne Kiss, who had renovated a deconsecrated synagogue in

the town of Samorin, Slovakia and now managed a small art gallery in

what looked to be a remarkable space. The couple invited me to

undertake a residency they would sponsor. I wrote to express my

gratitude and my main concern: given the recent events in my life, I

couldn’t guarantee that in two and a half weeks I would complete any

art whatsoever. I was impressed that they were unfazed by this prospect.

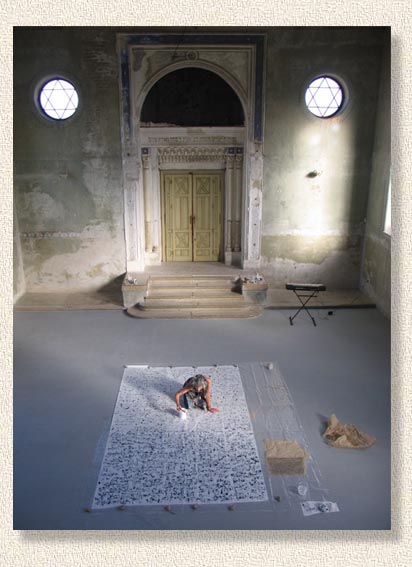

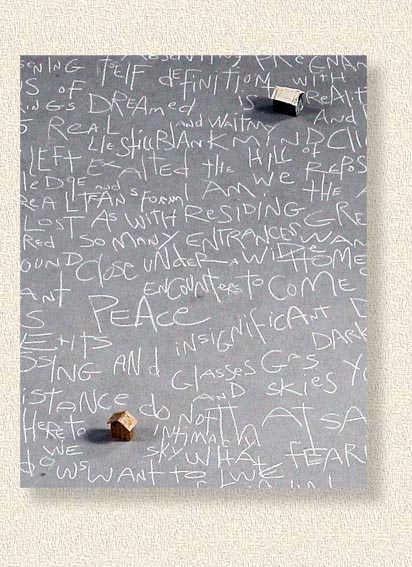

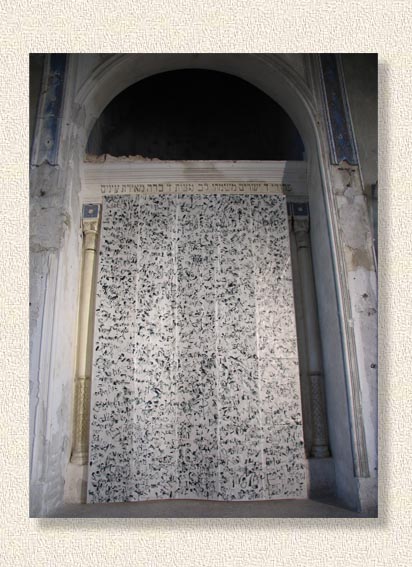

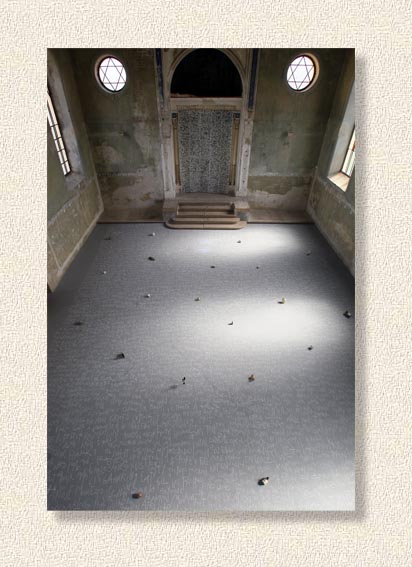

“We’re the catalyst,” they reassured me. “You’re the artist. Who knows what may happen?” “This is going to be all about home, “I told friends. “I’m leaving home to come home to myself again.” In May, 2013 I flew to Vienna and took a bus to Samorin, population about 12,000. The gracious Csaba and Suzanne spoke English and put me up in an extension of their home. The former synagogue itself was almost next door, built in the early twentieth century and abandoned when the Holocaust devastated European Jewry. Since then, perhaps at Suzanne’s initiative as a practising Buddhist, the Dalai Lama had stayed there. The interior preserved Hebrew inscriptions on the stone walls and Tibetan symbols had been applied to the ceiling. The floor was concrete. At some point during my stay I learned that I was a guest of the At Home Gallery, a name that was confirmation of what it had been and what it would prove to be for me. I chose to populate this spare, quiet place with small houses I constructed in the space itself from my companion roll of rice paper and materials found in a Slovakian equivalent of a dollar store.  I covered the floor in chalked words I associated with home.

Over the former altar, I hung a large, inscribed tapestry of rice

paper that continued my theme.

On the night of the “opening”, as twenty people hugged the walls and looked down from the entranceway, I danced between and around the houses to the accompaniment of a single saxophone, my feet slowly erasing the words as I moved, as did the feet of the audience.

When

I left Samorin. the words chalked on the grey floor had become clouds

and the scattering of houses floated on those clouds. The rest was

stillness.

|

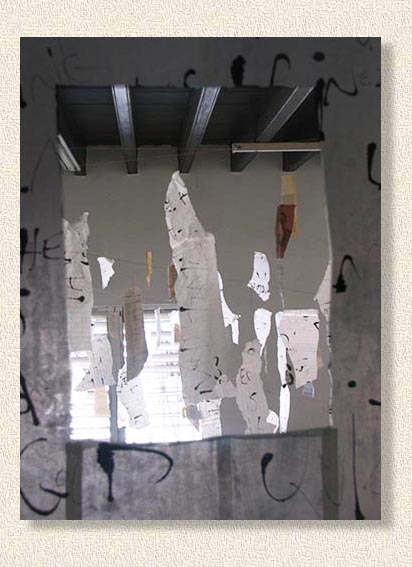

In 2013 Cuban artist

Tomas Aquilino linked me to other Cuban artists. I flew to Havana from

Montreal.

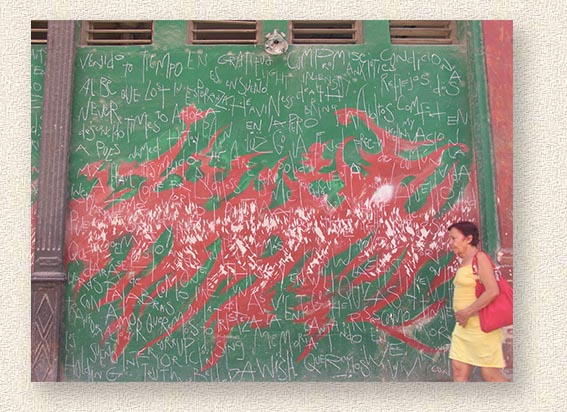

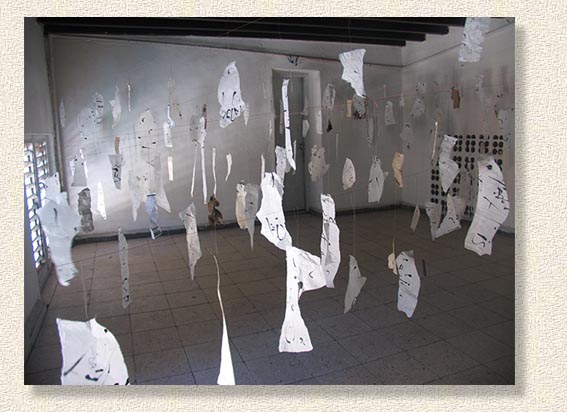

I arrive without a plan, without knowing where I’ll work or what that work will be. I have my roll of rice paper, my black ink, some chalk. I’m greeted by Tomas, a poet and gallerist, a ‘friend of a friend’, who has arranged my lodging in a ‘casa particular’. In time he becomes a real friend: a guide, a translator, and an assistant. He arranges a studio and exhibition space for my use and introduces me to several off-beat, passionate and dedicated artists who, though financially and materially compromised, dedicate themselves to the making of art, no matter the limitations and difficulties they encounter. The ‘studio’ is as bare as any I could have imagined: a doorless room at the top of a crumbling staircase. Peeling paint, a rusty fridge, a dirty cement floor, a small metal table, a florescent light, a slatted window through which polluted air and noise rise up from the street below. On the sidewalk, men play dominos on a folding table. An ice cream vendor pushes his wagon along, recorded circus music calling to the kids around. Downstairs, a windowless room with a bucket – our water source when needed. Everything is unfamiliar to me: the language, the poverty, the heat, the diesel-loaded air. I wander the streets, looking, taking in and slowly open myself to a kind of beauty unlike any I’ve known. There is a pervasive deterioration, a decomposing of everything: buildings, streets, courtyards, staircases, cracks. Electrical wiring hanging loose and dangerous. Laundry spread out on rope to dry in the open air. Teams of men moving in and out of doorways, spraying blue clouds of mosquito poison. Vendors call in repeating sing-song: garlic, bananas, cigars, coca cola. A group of young girls crowd their one-room school, backs to the open street-level door. I buy ten feet of string — as many lengths as I can get — from a vendor of odds and ends whose store is the size of a closet, with make-do shelves holding whatever stock she can get her hands on. I’m almost overwhelmed by the smells, the crowds, the cars, the dogs, the state of decay, and yet, and yet ... Something begins to take shape. I walk, absorb, then return to that empty room day after day. I keep picking up papers, writing on them with black ink, ripping and tearing theminto pieces: torn edges, accumulating random shapes. Every morning I read the poetry of Cuba’s revolutionary poets from a translated book I find in a used book shop, their lines sounding through my mind. Tomas tries to teach me Spanish and invites me to write in chalk on the red and green walls of an artists’ hangout. Someone brings a ladder. Up and down I go, writing in Spanish and English — words heard, seen, spoken around me through the days.  A policeman spends several minutes scrutinizing the process, suspicious that I might be polically motivated, that my words might hint at revolution or a rewriting of revolutionary history. Young teenagers giggle and point, excited by this artist woman’s unexpected and public antics. The day arrives when the work is done and ready for whatever word-of-mouth public might show up. Omar, the impoverished painter who works below and so generously made room for me, climbs the stairs to see what has taken place. On his way, he passes more writing — chalked words on the peeling walls of the hall and staircase announces the title of the installation he is about to see in both our languages: Havana: A Poetry In Ruins/Una Poesie in Ruinas. I’m waiting at the top. The entrance through the room’s only door has become a window through which he can look into the space beyond.   Omar positions himself and peers through the aperture. The papers are moving slightly in the heat.  His eyes fill with tears. I hear him say: "This is my Havana." |